А.П. Окладников, А.И. Мартынов

А.П. Окладников, А.И. Мартынов

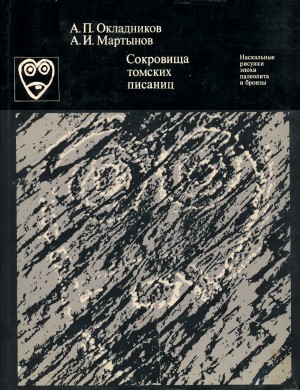

Сокровища томских писаниц.

Наскальные рисунки эпохи неолита и бронзы.

[ На суперобложке опечатка: «...палеолита...» вместо «...неолита...». ]

[ аннотация на клапане суперобложки: ]

Памятники первобытной культуры в наши дни всё больше приковывают к себе внимание самых разных людей — от археологов до историков искусства и художников включительно. Не будет преувеличением сказать, что содержание и особенно стилевая специфика древнейшего искусства сегодня приобретают во многом иной внутренний смысл, обнаруживая ряд созвучий с современными устремлениями эпохи. В этом лишний раз убеждаешься при знакомстве с богатейшей «коллекцией» наскальных рисунков эпохи неолита и бронзы, обнаруженных в Сибири, на реке Томи. Они сохранили для нас всю сложность своего смыслового содержания и притягательную красоту первобытного художественного реализма. В большинстве случаев рисунки передают облик и образ «хозяина тайги» — лося, а также других лесных животных: медведя, оленя, совы и т.д. Человек, тема его занятий и восприятия мира органично включились сюда в том же сложном контексте магического истолкования. В книге впервые публикуется около 500 таких рисунков. Авторы в увлекательной форме знакомят читателей с двухвековой историей изучения писаниц, а также с обширным кругом идей и мифологических представлений, составлявших основу содержания первобытного искусства.

Содержание

Предисловие. — 5

I. Из истории изучения томских писаниц. — 9

II. Галерея древних рисунков.

Томская писаница. — 23

Камень I. — 25

Камень II. — 30

Камень III. — 35

Камень IV. — 46

Камень V. — 49

Камень VI. — 72

Камень VII. — 96

Другие рисунки. — 117

Новоромановские Писаные камни. — 126

Камень I. — 126

Камень II. — 129

Камень III. — 131

Камень IV. — 134

Камень V. — 136

Тутальская писаница. — 143

Камень I. — 143

Камень II. — 162

III. Хронология и стиль томских писаниц.

Искусство. — 165

Древнейшие рисунки. — 176

Неолитические изображения. — 180

Рисунки эпохи металла. — 187

IV. Мир идей. — 193

Образ «хозяина тайги». — 194

Священные птицы. — 203

Антропоморфные фигуры и загадочные личины. — 208

Олень-солнце. — 221

Лодки в страну предков. — 229

V. Культурно-историческое место томских писаниц. — 237

Примечания. — 245

Список иллюстраций. — 253

Таблицы [ 1-38 ]. — 257

Summary. ^

The book describes the petroglyphs discovered on the banks of the Tom River between Kemerovo and Tomsk — splendid relics of prehistoric art.

One of them, the Tomsk site, has been known since the end of the 17th century and has been extensively discussed by Russian and Western authors. Two other sites — Tutalskaya and Novoromanovskaya — were discovered quite recently, in 1957.

The rock drawings of the Tom River were produced by the prehistoric hunters of the forest belt, who inhabited Western Siberia at the close of the Neolithic and in the Bronze and Iron Ages. We believe the earliest drawings to date from the 5th millennium B.C., whereas the latest are dated in the 1st millennium A.D.

The 4000-odd drawings of the three sites on the Tom River are of great interest inasmuch as they give us a glimpse of mankind’s early culture in its innermost manifestation. They give an insight into the world outlook, aesthetic ideas and ethical standards of the prehistoric hunters, revealing to us how they saw themselves and the surrounding world. Reflected in these works of art are the material production and the world outlook of our ancestors.

The Tom petroglyphs have a definite range of subjects, comprising mostly the forest animal life, and above all the elk; they have a distinctive way of presentation in side view, in a remarkably dynamic manner: we see elks walking calmly or tensely striding, running, standing alerted or dying. The artists, who were hunters, were able to portray the animals in different moods with amazing veracity but little detail — stressing only what was essential. This art was nurtured by the naive materialistic ideas and the requirements of the people’s social life and labour. It can be described as the art of primitive realism. Still, side by side with the realistic elements there is marked stylisation.

The rock drawings of the Tom River have much in common with those of the. Angara and the Lena and with the petroglyphs from the North of Europe. All these belong to the realm of forest hunters, which was immense. It embraced a host of different peoples who lived over a vast territory. The petroglyphs testify to the fact that despite territorial and ethnic differences, these peoples had remarkable affinities as concerns their imitative art, and consequently their world outlook. The images and ideas which arose on the Tom and the Angara often reproduce, down to the smallest detail, certain images and subject ranges of petroglyphs from the North of the European territory of the USSR and Scandinavia. They are based on “animal epics” and present the animals which were hunted — elks, deer, bears, as well as birds, snakes and anthropomorphic creatures. The Neolithic hunters and their Bronze Age descendants all over the North of Eurasia went on depicting, with remarkable tenacity, emblems of fertility, solar discs, boats and human feet, investing these images with profound meaning and conveying through them their understanding of the surrounding world and the universe.

We thus witness an amazing uniformity of outlook, which emerged among the people of the Neolithic inhabiting a vast area of several thousand kilometres. At the same time the imagery of Northern mythology penetrated far south; and conversely, the traditional ideas of cattle breeders and cultivators reached the North from the South. The contacts were of a permanent nature: not only productions skills, but ideas and views were exchanged. Thus, examining the subject-matter of the petroglyphs of Northern Eurasia, including the Tom site, we discover images resembling those inspired by the mythology of the civilisations of Ancient Egypt and Western Asia.

There is a number of reasons to account for this. Similar ideas could have emerged due to convergence; also, they could be borrowed. There never was a Chinese Wall between peoples. Ideas that were kindred and comprehensible to people spread widely in all epochs, irrespective of territorial, economic, ethnic and language distinctions and all kinds of boundaries. The concrete-materialistic outlook, characteristic of that remote age, was a good basis for the spread of similar ideas. The destruction of the old tribal boundaries, of isolation and the primitive way of life at first stimulated the spread of advanced techniques of stone working, and later the spread of bronze. The use of metal wrought a virtual revolution in the economic life of the steppe tribes. It also exerted an influence on their neighbours who lived close by in the forests of Northern Eurasia. The use of bronze stimulated the manufacture of new artifacts, enhancing man’s productivity and modifying his ideas of his environment. This unity — or community — is clearly traceable in the main components of evolution; the conditions of life, the economy, the course of historical development and,

(250/251)

as will be seen from the above, the ideology of the peoples who inhabited the forest belt of the North of Europe and Siberia in the Neolithic and the Bronze Age. Problems of the community of culture of the peoples living in the North have attracted the attention of many researchers both in the Soviet Union and abroad. It has been proved beyond doubt that there was a culture zone stretching along the subarctic region whose uniformity even in the early period is borne out by archeological finds. The forest belt of North-Eastern Europe and North Asia is seen as a similar zone once the basic features of cultural development are examined.

There were several attempts to find a single centre from which the petroglyphs of the Arctic Neolithic may have spread. Thus, H. Brogger believed that they emerged not from the Neolithic of South Scandinavia but “from the southern regions of Finland and Russia”. Brogger thought that this art had taken shape on the basis of a common “Stone Age art of the Russian Baltic lands”, Finland and Scandinavia; this community had as its bearer a distinctive people, who had made its way from Russia to Sweden and thence to Norway via Finland and the Eastern Baltic.

This community was regarded as far more embracive by A. Bjorn, who noted that the northern petroglyphs displayed an affinity with Siberian-Mongolian art. From this Central Asian centre the hunters’ monumental art reached the West in two waves: one arrived via Central Europe, the other via Kola Peninsula and Northern Norway, and also via the Bering Strait (thus reaching North America).

It is hardly advisable to look for one centre or for a mass migration of the ancient population in trying to account for the affinity of the petroglyphs of North Europe and Asia. The reasons for the community should be sought in other factors — above all, in those aspects of the people’s life which mould their outlook. Of primary importance is the uniformity of the natural setting — the forests of the North of Europe and Asia in which countless generations of hunters had lived and from which they drew their sustenance. The common features of the hunters’ economy accounted for the rise of similar features of material culture among the forest dwellers of the North of Europe and Asia: specific types of arrowheads, bone harpoons, the shapes and decorative patterns of pottery. The forest with its animal life, hunting and the common culture elements affected the outlook of the ancient forest-dwelling hunters, their understanding of the source of life, the act of death, the role of the sun, and their idea of the universe.

That is why all the petroglyphs from this vast area, in spite of their distinctions, depict the animals which were the quarry of the Neolithic hunters, their hunting techniques, weapons and means of transportation. Sometimes they are complete narratives based on real events experienced by the artist or his tribesmen. Stored in the mentality of the prehistoric hunters of the taiga forests was the age-old experience of their ancestors and a wealth of knowledge of the surrounding world; they had reached the stage of generalisation and abstraction.

In addition, the petroglyphs show that the early hunters, lost among the boundless forests, were able to comprehend the beautiful and to convey it in their own distinctive manner. Their profound power of observation is clearly discernible in the drawings. Knowledge of the animals’ ways was an essential feature of the primitive realistic art of petroglyphs.

The Tom rock drawings convey in a spontaneous materialist form the basic ideas that stirred people in that remote age. Being complete narrative scenes, they are easily distinguished from the mass of other representations. One group of drawings deals with the mysterious act of animal procreation, of the beginning of a new life within the body of a female elk. These scenes are many and diverse, ranging from naive depictions of coupling animals to large symbolic pictures (e.g., the third rock of the Tom site). It shows a herd of female elks, walking close to one another, and a male figure with a huge phallus towering over them. In some cases this male figure has animal features. One drawing shows an anthropomorphic creature with a rattle in its hands; it greatly resembles the image of Thor (Donar), the god who occurs in Scandinavian mythology and is depicted on the petroglyphs. Another group of drawings deals in great detail with the hunting of elks, presenting all the hunting techniques of the forest dwellers. There are many isolated drawings showing elks with arrowheads, dying elks with javelins sticking from their backs, animals caught in a noose. Of special interest are the large narrative scenes. One shows the chase, another — the kill.

The petroglyphs had a concrete cult purpose: they were made on the sites where rituals were performed. Even much later, as late as the 20th century, individual peoples still regarded certain rocks as cultic. Lapps, Khanty, Evenks, Buryats and other peoples had sacred rocks, which, they believed, gave hunting and fishing luck. These rocks were smeared with blood and given animate names.

The fact that the rocks bearing the drawings face south — quite an important detail — likewise stems from their

(251/252)

cultic purpose. K.D. Laushkin was the first to notice this with regard to the Onega petroglyphs. It then transpired that the petroglyphs of the Urals, too, are sited on rocks facing south. A similar location is characteristic of the Tom petroglyphs, which are drawn on the rock surfaces facing the sun. This gives us a better idea not only of the general meaning but also of the purpose of the rocks and the drawings.

There is another characteristic closely connected with the southern exposure of the rocks: all the three Tom sites have platforms before the vertical rocks bearing the drawings. The collective mentality of prehistoric man who depended on seasonal hunting, was bound to incorporate a cultic, cosmic outlook — a form of awareness of the dependence of all animals and man himself on nature. It is clear today that the choice of place where the solar rites were performed was quite important. The choice of rocks to bear the drawings was far from accidental. Ceremonies, sun magic and sun rituals, rituals of ancestor, sacred animal and totem worship were performed on the sunlit platforms before these rocks. During these festivities myths were made up and drawings put on the rocks. The ceremonies probably had common features among different peoples, notwithstanding the considerable chronological, geographical and ethnic gaps.

Yet it would be wrong to look only for the common features which emerged as a result of a similar structure of the economy and a similar outlook. The petroglyphs are far from a drab collection of drawings dealing with the same, identically treated subjects. On the contrary, there are noticeable distinctions even between close-lying sites. The distinctions are still more marked if we compare the petroglyphs of territories lying far from one another, e.g. Karelia, the Urals, Western Siberia, Eastern Siberia, etc. In some places the petroglyphs can be traced to a concrete ethnic group. The petroglyphs of the Urals, for example, are closely linked with the art of the Khanty and Mansi and thus belong to the ancient Finno-Ugric population of the Urals. A similar connection can be traced, with equal clarity, between the ancient art of the Amur River area and modern Nanaian ornamental designs. The later petroglyphs of the Lena River link perfectly with the art of the Kurykan and the later Turkic-speaking peoples of South Siberia; the later petroglyphs from the Lower Angara area (drawn in ochre), representing horses and riders, solar emblems with rays and primitive human figures, reveal a very close affinity with the art of the ancient Samoyed tribes and the forest-dwelling Turkic peoples of Siberia.

It is beyond doubt that some details of the Tom petroglyphs link them with the Western petroglyphs; these details do not occur in the rock drawings of the Angara and the Lena. Notable in this respect are boats with elk figureheads. This detail, characteristic of European rock drawings, hardly ever occurs on East Siberian petroglyphs. The figure of the skier, too, closely resembles its counterparts from Zalavruga on the White Sea and from Norwegian sites. The images of water birds, elks and anthropomorphic creatures show the same likeness. All this links the petroglyphs of Tom with those of the Urals and North-East Europe. It also testifies to the fact that the Tom petroglyphs belong to the relics of the ancient Urals-Siberian (Ugrian) Stone-and Bronze-Age community.

Yet the Tom petroglyphs also show unmistakable traces of the influence of the culture of South Siberia’s steppe peoples. This is primarily due to direct geographic proximity. The Tom petroglyphs are located in an area that was a junction of cultures, close to the South Siberian steppes and their inhabitants. This probably accounts for the forceful image of the deer with shining antlers, which is especially wide spread in Southern mythology and the imitative arts of the cultures of the Scythian world in the 1st millennium B.C.; for the frequency of solar emblems, amazingly close in shape and meaning to the solar emblems of Andronovo and Tagarskoye art; and, finally, for the anthropomorphic figures resembling those of Okunevo culture.

The petroglyphs of Tom also incorporate distinctive images which testify to the fact that these petroglyphs belonged to a specific, concrete group of the ancient population which had its own ideas sprung from the common world outlook of the forest hunters of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age. These distinctive features are revealed above all in the anthropomorphic figures; in the way the animals’ bodies are subdivided; the marvellous representations of the eagle owl and the long-legged birds; the concrete hunting scenes; the unique, stylised figures of dancing men with bird’s beaks and bird-like extremities; the small stylised figures of men with two lines running upwards from their heads.

It is these highly distinctive features that in the final analysis constitute the special value of the Tom petroglyphs. The Tom rock drawings graphically illustrate the evolution of the way of life and culture, the aesthetic ideas and world view of the forest tribes of Western Siberia’s south-eastern territory and their intricate cultural and ethnic ties with other peoples.

|