А.Г. Фурасьев, Е.А. Шаблавина

А.Г. Фурасьев, Е.А. Шаблавина

Концешти:

княжеское погребение

эпохи Великого переселения народов.

// СПб: Изд-во Гос. Эрмитажа. 2019. 244 с. ISBN 978-5-93572-848-9

[ аннотация: ]

В книге впервые публикуется полный свод материалов археологического памятника эпохи Великого переселения народов — княжеского погребения у села Концешти. Коллекция вещей, хранящаяся в Государственном Эрмитаже, спустя более двухсот лет с момента находки стала объектом пристального всестороннего изучения. Новые данные, полученные авторами, позволяют интерпретировать комплекс как захоронение знатного варварского предводителя, долгое время находившегося на римской военной службе. Будучи выходцем из среды восточногерманских племён Северного Причерноморья, современником Германариха и Аммиана Марцеллина, он принимал участие в битвах Римской империи с гуннами и персами в 360-х — 380-х годах. Погребальный инвентарь (украшения, конская упряжь, парадная серебряная посуда) и эпиграфические данные отразили этапы карьеры этого человека, протекавшей на фоне исторических коллизий второй половины IV века в Центральной Европе.

Книга предназначена для специалистов: историков, археологов, преподавателей и студентов, а также для широкого круга читателей, интересующихся историей.

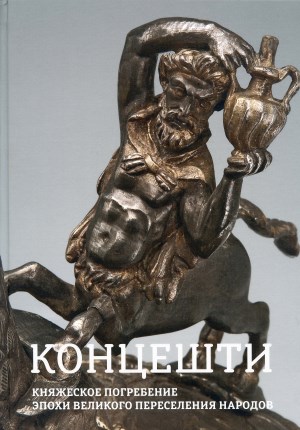

На обложке:

Ваза-амфора. Вторая половина IV в. Серебро; позолота.

Деталь: ручка в виде кентавра.

Государственный Эрмитаж.

Оглавление

Глава 1. История открытия памятника (А.Г. Фурасьев). — 9

Глава 2. Научный обзор вещевого комплекса (А.Г. Фурасьев, Е.А. Шаблавина). — 20

Глава 3. Датировка и этнокультурная принадлежность погребения (А.Г. Фурасьев). — 178

Глава 4. Итоги и перспективы исторического поиска (А.Г. Фурасьев). — 187

Приложения.

Приложение 1. Химический состав металла предметов (К.С. Чугунова, С.В. Хаврин). — 198 (См. на academia.edu)

Приложение 2. Реставрационный поддон XIX века для серебряного блюда (К.С. Чугунова). — 218

Приложение 3. Письмо В.И. Милашевича А.К. Разумовскому. — 221

Приложение 4. Ордер Придворной конторы. — 224

Принятые сокращения. — 227

Литература и источники. — 228

Предисловие. ^

Немногим более двухсот лет назад рядом с местечком Концешти (или Кончешть) на правом берегу реки Прут (совр. Румыния) при случайных обстоятельствах был обнаружен один из самых ярких археологических памятников эпохи Великого переселения народов — богатое «княжеское» погребение, которое сразу же попало в поле пристального внимания исследователей, учёных и просто любителей древности (ил. 1). Благодаря тому, что бо́льшая часть находок в 1814 году поступила в Императорский Эрмитаж, этот комплекс стал достоянием публики и научных кругов. Несмотря на уникальность памятника и его огромное научное значение, подтверждением чему служит его упоминание чуть ли не в каждой археологической или искусствоведческой работе, связанной с проблематикой периода Великих миграций в Европе, за прошедшие двести лет так и не появилась исчерпывающая публикация всех материалов из этого погребения. Незначительная часть коллекции, а именно мелкие обрывки золотой фольги и бесформенные обломки неопределённых предметов, вообще до сегодняшнего дня оставалась неразобранной. При этом литература, посвящённая наиболее интересным предметам, огромна. Общая характеристика памятника и различные аспекты его изучения также довольно часто становились объектом специальных исследований.

Ряд проблем, связанных с находками из Концешти и определением места этого комплекса в культурно-хронологической системе древностей, решить пока не удалось. По-прежнему актуальными остаются вопросы целостности комплекса, датировки отдельных его составляющих, этнокультурной принадлежности погребённого, истоков представленных здесь погребальных традиций. Одной из причин такой незавершённости, на наш взгляд, является отсутствие всеобъемлющей публикации материалов памятника, детально отражающей его разнообразный состав, не ограниченный шедеврами позднеантичного искусства, которые часто перетягивают на себя всё исследовательское внимание. Исходя из этого, мы считаем своей первоочередной задачей введение в широкий научный оборот всего состава находок из Концешти, включая и мельчайшие обломки вещей, поддающиеся хоть какой-то атрибуции, вместе с подробным их описанием, с использованием всей доступной информации. Та часть актуальных научных данных, которая уже опубликована другими специалистами и общедоступна, будет изложена кратко. Основное же внимание мы уделим новым исследованиям и новым фактам, которые нам удалось установить. К таковым относятся выявленные мелкие предметы из фольги, некоторые ранее не замеченные характеристики ряда предметов, эпиграфические данные, итоги технико-технологического анализа большинства находок, а также результаты лабораторного рентгено-флюоресцентного анализа вещей.

Избранная нами форма изложения в виде последовательного и подробного описания вещей (наподобие каталога) как нельзя лучше соответствует поставленным задачам. Это позволит исследователям, во-первых, всегда иметь под рукой свод находок из данного комплекса с полным указанием и анализом источников, во-вторых, быстро найти всю необходимую информацию как по каждому предмету в отдельности, включая литературу о нём, так и по общим проблемам их изучения, поскольку внутри каждой позиции все

(6/7)

Ил. 1. Находки из Концешти.

Экспозиция «Европа в эпоху Великого переселения народов» в Кутузовской галерее Зимнего дворца. Фотография. 2018.

сведения структурированы. Кроме того, результаты анализов химического состава предметов из металла приведены в Приложении 1; результаты рентгено-флюоресцентного анализа (РФА) сведены в таблицу (с. 214, табл. 2).

Авторы считают своим долгом поблагодарить всех коллег из разных учреждений и стран, оказавших нам помощь в процессе подготовки данного исследования: Светлану Рябцеву и Ларису Чебану (Институт культурного наследия Академии наук Республики Молдова), Романа Рабиновича (Высшая антропологическая школа, Молдова), Станко Трифуновича и Тияну Станкович-Пештерац (Музей Воеводины, Сербия), Михаила Михайловича Казанского (Национальный центр научных исследований Франции), Андрея Юрьевича Алексеева и Юрия Александровича Пятницкого (Государственный Эрмитаж). Мы также с благодарностью вспоминаем помощь, оказанную нам Сергеем Ремировичем Тохтасьевым, к великому прискорбию, безвременно ушедшим из жизни.

Особую сердечную признательность и слова искренней благодарности мы выражаем нашим старшим коллегам-наставникам — Ирине Петровне Засецкой и Рафаэлю Сергеевичу Минасяну (Государственный Эрмитаж).

Фотографирование экспонатов коллекции и проведение рентгено-флюоресцентного анализа находок были выполнены благодаря финансовой поддержке Российского гуманитарного научного фонда в рамках совместного с Национальным центром научных исследований Франции проекта 2009 года «Княжеское погребение у села Концешти».

Summary. ^

One of the most fascinating archaeological sites dating to the Great Migration Period, the rich ‘princely’ grave located on the right side of the Prut near Concesti (modern Romania), was discovered in 1812.

Despite the enormous scientific importance and uniqueness of the site, the materials found in this grave have not been covered by any comprehensive publications over the past 200 years; the available literature fails to provide a detailed description of the items unearthed in Concesti, with the exception of the Late Roman masterpieces. As a result, questions still abound as to the integrity and composition of the grave goods, their dating, the ethnic and cultural definition of the deceased as well as the origins of the funeral traditions. Our priority purpose is therefore to introduce the archaeological research community to the entire collection of Concesti finds including the smallest identifiable artefact fragments, as well as to provide the detailed description of the objects. The key focus of our publication is the recent studies conducted on the site and the new evidence we have obtained as a result of our research. The latter includes previously unknown small items made of foil, hitherto unnoticed features of certain artefacts, new epigraphical data, results of the technological analysis and X-ray fluorescence analysis of the artefacts.

In terms of their origins, the Concesti grave goods can be segregated into three groups, whose importance extends far beyond the ethnocultural attribution and dating of the site. Initially, researchers identified just two groups of finds (Barbarian and Greek-Roman); later, however, the Barbarian artefacts were classified into two subsets, one unmistakably associated with Hun nomadic traditions, the other supposedly East Germanic. This approach has received its most well-founded treatment in Mikhail M. Kazansky’s works. At the same time, Kazansky emphasises the arbitrariness of this classification and the close interrelations between the three traditions within a unity culture of the European Barbarian elite.

The principal group of late Roman finds is quite distinct and leaves no doubt as to its origins. The group consists of all the silver artefacts recovered, namely a helmet, a chair and some tableware, possible also the gold cloisonne decorations.

In all probability, the silverware found among the grave goods formed part of a formal set rather than a random collection. As follows from the interview with the persons discovering the site, the burial originally contained more metal vessels. There are no reasons to put this eyewitness account to serious doubt. The site discoverers also mentioned two silver dishes, one of which had several ‘gold goblets’ placed on it. In all probability, the discoverers were referring to miniature ‘bowl cups’, more likely gilded rather than actually made of gold. The whole set, therefore, originally comprised three silver dishes (an amphora, a situla and a beaker) as well as several small cups — a total of at least eight objects, just half of which have been retrieved. The best known hoards of late Roman silver objects dating from the mid-fourth — early fifth century (Seuso, Mildenhall, Kaiseraugst, Esquiline Hill) are quite similar to the Concesti grave goods in both qualitative and quantitative terms.

The Late Roman artefacts from Concesti, including the helmet, the amphora, the beaker, the dish, inlaid belt tips and an eagle-shaped plaque, date from the period between the mid-fourth — early fifth century. The oldest of the objects is the situla, which may have originated in the third or the first half of the fourth century. The chair has a much broader dating.

The chemical composition of the Roman metal objects (the vessels, the chair, the helmet and the reverse side of the eagle plaque) is strictly homogeneous (Table 2). The material contains 93(94)% — 98% silver — a feature typical of Late Roman or Early Byzantine silverware

(241/242)

(especially formal tableware sets) which is considered to have been made from Roman coin silver.

A second group of finds is associated with the nomadic culture of the European steppes during the Hun period. Most of these are trimmings from bridle straps, with or without polychrome ornaments, as well as parts of plaques with stamped fishscale-like decor, including a fragment of saddletree plaque made of gold foil. All of these finds are functionally related to horse equipment. In all probability, the buried horse may have been saddled and bridled; all the artefacts representing this ethnocultural group were located on the skeleton of the animal. In our view, these artefacts are of secondary relevance to the ethnocultural attribution of the burial, although many Western European researchers have identified this set of finds as ethnically definitive.

The polychrome trimmings as well as the foil plaques can be identified as early Eastern European artefacts of the Hun origin dating from the late fourth — first half of the fifth century. The starting point of the period corresponds to the beginning of the Hun invasion in 375 AD. The artefacts therefore enable us to narrow down the time of the burial to the last quarter of the fourth or early fifth century. The presence of fourth-century artefacts, including those originating in the middle and latter half of the century (the helmet, the amphora and the dish) or, possibly, even in the first half (situla) led most researchers to identify the burial as originating at the turn of the fifth century. The dating of the burial as near 400 AD (suggested in many publications), despite its conventionality, appears the most plausible. However, the epigraphical data from a large silver dish suggests the Concesti burial most likely dates to the late fourth century or, more specifically, the 380s-390s AD.

A third group of finds, possibly linked with the East Germanic culture circle of the North Pontic origin has a broad dating but is highly pertinent to the ethnocultural attribution of the funerary complex, primarily owing to the close connection of the finds with the burial rite. Of particular note here are the gold diadem (fig. 119), the foil appliques (figs. 128-130) and the facial plates (fig. 138).

The burial was found to contain remains of a degraded garment (‘a tunic embroidered with gold and stones’), with several ‘gold sticks’ recovered from the grave surface. Leonid A. Matsulevich was the first to convincingly identify the ‘gold stick’ fragments as remains of gold appliques, although no material evidence has been available to support this claim until the present. The very presence of appliqued garments in the Concesti burial used to be put to doubt, but mistakenly so.

The second and third elements mentioned above which pertain to the funerary subculture of the Greek and Bosporan origin are a gold burial diadem and eye caps; the elements appear somewhat archaic for that period if regarded as originating from ancient Greek and Roman culture of the Mediterranean and Pontic Region. However, later manifestations of this tradition borrowed by the mixed Greek-Barbarian population of the North-West Black Sea Region persisted over the first third or even first half of the fifth century.

The recovery of gold appliques and eye caps from the Concesti grave is a crucial ethnocultural, social, territorial and chronological feature, which, regrettably, was identified only a short while ago. The finds should add to the importance of already well-recognised Pontic or, more accurately, Crimean-Bosporan cultural impact on the interesting Migration Period site which is Concesti.

The artefacts of the Bosporan origin include the gold torc (fig. 97) and part of the gold plaques on a copper base; the plaques carried some stamped decor (figs. 105, 121-123). The attribution was mainly based on the technical features and the metals used in the artefacts (gold and copper). It would be appropriate to emphasise yet again the stunning accuracy of detail in the amphora decor representing polychrome bridle sets typical of the Bosporan area in the first half of the fourth century (fig. 18). It may also be suggested that the grave contained parts of two heterogeneous bridle sets, one of the Hun (figs. 111-117), the other of the North Pontic origin (fig. 105). The presence of two bridles in the burials has been identified as a relatively consistent funerary tradition, in rich Late Antique

(242/243)

burials of the Bosporan area such as the Gold Mask Burial in Kerch.

There are some other important elements of the funeral rite worthy of note, namely, the stone vault and the accompanying horse burial. These elements were studied by Leonid A. Matsulevich, who noticed their striking resemblance to the fifth-century Germanic ‘commander’ burial in Bolshoy Kamenets. The synchronic Concesti and Bolshoy Kamenets sites are very similar in many respects and may therefore be regarded as historically and culturally related. The details of the burial rite mentioned above were analysed in depth in their relation to the broader European context by Mikhail M. Kazansky, who argued that these and a number of other features confidently place the Concesti burial in the privileged culture of early Barbarian client states emerging at the borders of the Roman Empire. The combination of these elements in the same internment points strongly to the North Black Sea Region, most likely the Bosporus.

Territorially, chronologically and ethnoculturally, the Concesti burial occupies the middle ground between the late fourth — early fifth century syncretic Greek-Barbarian world of the North Pontic Region and the heterogeneous Germanic-Alan world of the Lower and Middle Danube Region, whose elite subculture is represented by the traditions of the Untersiebenbrunn horizon.

As for the social and military status of the commander buried in Concesti, the principal clues for its identification are, firstly, the Late Roman helmet of an officer of the guard (fig. 84), and secondly, the previously unnoticed epigraphical evidence on the silverware. All researchers from Leonid A. Matsulevich onwards have mentioned a single weight inscription in Greek on the situla (fig. 40). Upon close examination, we discovered another two weight inscriptions (fig. 58) on the same vessel (one Greek, one Roman), together with yet undecoded signs (a monogram?), a graffito with a single (weight?) sign on the amphora (fig. 39), and a complete dedicatory five-line text at the bottom of a large dish (fig. 70).

The inscriptions on the dish contain the dedication Jupiter, Best and Greatest [Iovi optimo maximo] traditional for Latin religious epigraphy; one inscription mentions Jupiter of Heliopolis [Iovi optimo maximo Heliopolitano], and one refers to Jupiter the Protector. In addition, an overturned pentagram and several near-illegible Latin (?) letters are visible in the centre of the tray. It is noteworthy that the dish is likely to have originated in the fourth century, a time of rapidly growing importance and role of Christianity in the Roman Empire. The pagan dedications may have appeared during a brief period of pagan revival in the reign of Julian the Apostate. One particularly interesting piece of epigraphical evidence is inscription 5 [Iovi o[ptimo] prot[ectori]]. The title ‘Protector’ as an epiclesis of Jupiter looks quite archaic as this rare epithet only appeared in inscriptions of the republican period. From the turn of the fourth century onwards, the term came to be associated with a unit of imperial bodyguards known as Protectores Domestici. Its use on the vessel suggests a close connection of the graffito authors (authors) with the military environment. Inscription 5 yields to a traditional interpretation To Jupiter, the Best Protector or may read as To Jovian, the Best Protector. Jovian, commander of the Protectores guards, was declared emperor following Julian’s death during the Persian campaign (363 AD).

The evidence obtained as a result of this study has enabled us to make two important conclusions relating to the chronological and ethnocultural status of the Concesti site. The new epigraphical findings have shown that the deceased may have been more closely tied with the Roman military and cultural environment than it appeared before, and his links to syncretic Bosporan Greek-Barbarian (Germanic?) aristocracy of the mid-fourth century are almost without doubt.

Translated by Natalia Magnes.

|