[ êàòàëîã âûñòàâêè ]

[ êàòàëîã âûñòàâêè ]

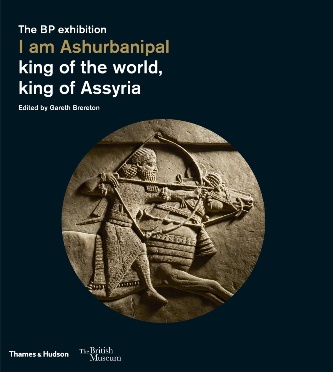

I am Ashurbanipal: king of the world, king of Assyria.

/ Ed.: Gareth Brereton. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. / British Museum. 2018. 348 pp. ISBN 978-0-500-48044-1

In 669 BC Ashurbanipal inherited the world's largest empire, which stretched from the shores of the eastern Mediterranean to the mountains of western Iran. He ruled from his massive capital at Nineveh, in present-day Iraq, where temples and palaces adorned with brilliantly carved sculptures dominated the citadel mound, and an elaborate system of aqueducts and canals brought water to the king's pleasure gardens. Ashurbanipal, proud of his scholarship, assembled the greatest library in existence during his reign. Guided by this knowledge, he defined the course of the Assyrian empire and asserted his claim to be 'king of the world'.

Beautifully illustrated and written by an international team of experts, this book features images of objects excavated from all corners of the empire. The British Museum's unrivalled collection of Assyrian reliefs brings to life the tumultuous events of Ashurbanipal's reign: his conquest of Egypt, the crushing defeat of his rebellious brother in Babylon and his ruthless campaign against the Elamite rulers of south-west Iran.

"I am Ashurbanipal: king of the world, king of Assyria" provides an illuminating account of the Assyrian empire told through the story of its last great ruler, and highlights the importance of preserving Iraq's rich cultural heritage for future generations.

With 325 illustrations.

Contents

Sponsor’s foreword. — 6

Director’s foreword. — 7

1. Nineveh: the Centre of the World.

I AM ASHURBANIPAL, KING OF THE WORLD, KING OF ASSYRIA.

Gareth Brereton. — 10

ASHURBANIPAL’S PALACE AT NINEVEH.

Julian Edgeworth Reade. — 20

LIFE AT COURT.

Paul Collins. — 34

THE ASSYRIAN ROYAL HUNT.

Julian Edgeworth Reade. — 52

ASHURBANIPAL’S LIBRARY: CONTENTS AND SIGNIFICANCE.

Irving Finkel. — 80

KNOWLEDGE: THE KEY TO ASSYRIAN POWER.

Jon Taylor. — 88

2. Ashurbanipal’s Empire.

THE NEO-ASSYRIAN EMPIRE.

Gareth Brereton. — 100

THE LEVANT AND ASSYRIA.

Jonathan N. Tuââ. — 118

CYPRUS AND ASSYRIA.

Thomas Êiely. — 138

THE KINGDOM OF URARTU.

Paul Zimansky. — 154

WESTERN IRAN IN THE IRON AGE.

Yousef Hassan Zadeh And Jîhn Ñurtis. — 166

SUSA AND THE KINGDOM OF ELAM IN THE NEO-ELAMITE PERIOD.

Francois Bridey. — 180

3. Violence into Order.

ASHURBANIPAL’S CAMPAIGNS.

Jamie Noyotny. — 196

READING ASHURBANIPAL’S PALACE RELIEFS: METHODS OF PRESENTING VISUAL NARRATIVES.

Chikako F. Watanabe. — 212

THE BATTLE OF TIL-TUBA IN THE SOUTH-WEST PALACE: CONTEXT AND ICONOGRAPHY.

Davide Nadall. — 234

THE BATTLE OF TIL-TUBA CYCLE AND THE DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE.

Ronnie Goldstein and Elnathan Weissert. — 244

4. Collapse, Rediscovery and Revival.

THE FALL OF ASSYRIA AND THE AFTERMATH OF THE EMPIRE.

John Magginnis. — 276

NINEVEH REDISCOVERED.

Julian Edgeworth Reade. — 286

ASSYRIAN REVIVAL.

Henrietta McCall. — 300

Notes. — 315

Further reading. — 322

King lists. — 334

Contributors. — 336

Picture credits. — 338

List of lenders. — 340

Acknowledgments. — 341

Index. — 342

(/312)

THE FUTURE OF IRAQI CULTURAL HERITAGE UNDER THREAT ^

Jonathan N. Tubb, Falih Almutrb and Sebastien Rey

In 2014, in response to the appalling and senseless destruction of cultural heritage in the Middle East at the hands of Daesh, the British Museum, working closely with Iraq’s State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH), devised a training scheme that was intended to provide maximum benefit to its employees in dealing with the aftermath of the devastation. Known as the Iraq Emergency Heritage Management Training Scheme, or more simply the Iraq Scheme, it was fortunate in securing generous funding from the British Government, allowing a five-year programme to be developed, starting in 2016. During the course of the Scheme, fifty SBAH professionals, six to eight at a time in six-month cycles, will be fully trained, both in the UK, mainly at the British Museum, and also in the field in Iraq at two specially selected excavation sites, where the participants are able to put into practice what they have learned in theory. In addition to providing ideal venues for the training programme, the excavations at Darband-i Rania, in Kurdistan, and Tello, ancient Girsu, in southern Iraq, have developed into major research projects in their own right and ones to which the participants make a positive contribution, not only by physically excavating, but also through engaging in all aspects of the post-excavation processes, including drawing and photographing finds and writing sections for the published reports.

The Scheme delivers state-of-the-art training in all aspects of archaeological fieldwork, from geophysical and geomatic surveying and documentation to complex excavation methodology. Sophisticated techniques of digital photography (object and site) are also taught, as are the use of satellite imagery, principles of conservation, and, perhaps most importantly, sustainable approaches to site management. Having secured the necessary permissions from the Iraqi authorities, drone technology has also been added to the training programme, and the use of drones at the Scheme’s two excavation sites has proved to be of outstanding value, both in terms of comprehensive data recording and in revealing features otherwise invisible on the ground. A further development has been the initiation of a restoration project at Tello, where the participants are learning the principles of, and contributing to, the consolidation and ethical reconstruction of what may be the world’s earliest bridge, a Sumerian mudbrick structure dating to the third millennium BC.

The Iraq Scheme is widely acknowledged, in the UK, in Iraq and internationally, as providing one of the most significant contributions to the collective effort to protect and preserve cultural heritage in the Middle East, and is starting to have a real impact on the situation in Iraq. This was recognized in February 2017 during a two-day International Conference on the Safeguarding of Cultural Heritage in Liberated Areas of Iraq, held at UNESCO’s headquarters in Paris, when the then Director General, Irina Bokova, in describing the damage to heritage sites in Iraq as even greater than had been feared, applauded the British Museum’s initiative. Present at the conference were two of the current writers: Sebastien Rey, one of the Scheme’s senior archaeologists and Director of the Tello excavations, and Falih Almutrb, one of the programme’s first graduates, who, on the basis of

(312/313)

having completed the training, has been appointed Director of the Nineveh office with responsibility for some of the worst affected sites including Nineveh itself, Nimrud, Hatra and the severely damaged and ransacked Mosul Museum. It is surely an endorsement of the Scheme’s overarching aims, that three of its participants have been appointed to senior positions in the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage of Iraq, charged with the assessment and stabilization of reclaimed sites in their respective provinces. In 2014, at the height of Daesh’s self-proclaimed ‘caliphate’, thousands of archaeological sites throughout Iraq were under the control of the organization. According to Vice-Minister Qais Hussein Rasheed, in the Mosul region alone, at least sixty-six sites have been destroyed, some turned into parking lots. Places of worship have suffered massive destruction and thousands of manuscripts have disappeared from archives and libraries.

The damage to Nineveh and Mosul has been very severe. Eighty per cent of the site of Nimrud has been destroyed and Nineveh has been seventy per cent destroyed. Violent extremists systematically dug tunnels in Mosul and other heritage sites in search of antiquities to sell on the Internet and black market: heritage converted into weaponry.

Nineveh, one of the most important archaeological sites in the Middle East, existed as a city controlling a strategic crossing of the Tigris from deep prehistory. With the rise of Assyria it became a cosmopolitan centre, reaching its zenith as the capital of the empire in the seventh century BC, host to an array of palaces, temples, mansions of the elite and military installations.

Daesh devastated it, together with the Mosul Museum, smashing sculptures and destroying its very fabric. They bulldozed part of the walls of the ancient city and destroyed a number of gates which had been excavated and restored. In the Nergal Gate they mutilated the magnificent winged bulls that guarded the entrance. Nebi Yunus, the site of the ancient arsenal palace of the Assyrian empire, has been discovered to be far more damaged than had been expected. It has been severely disrupted by tunnelling, to the extent that the entire site is in danger of collapse.

Among all this dreadful news there is a glimmer of something positive. In the case of Nebi Yunus, it seems that Daesh were driven out of east Mosul just in time. What the liberators found was a network of tunnels, largely following the course of ancient sculptures which lined the palace walls. While these tunnels have been hugely damaging to the archaeology of the mound, it appears that Daesh did not have time to loot or destroy the sculptures. The discoveries in the tunnels — reliefs, sculptures and cuneiform slabs — are indeed spectacular. The reliefs are truly exceptional, depicting religious and cultic scenes, priests and what appears to be a goddess or high-priestess. Some carved panels with priest figures were found upside down, suggesting they had been reused in a monumental mudbrick structure, possibly a palace (or a palatial sacred quarter). The Iraqi armed forces also found in the tunnels a well-preserved lamassu, or human-headed winged bull, flanking the palace gateway. It is significant that on the basis of photographs taken of it, the colossal protective spirit is burnt, which is consistent with the pattern of targeted destruction (of gates and temples) of 612 BC, marking the fall of Nineveh. Other important finds include some unique rock reliefs with a completely new iconography.

Nimrud, the Assyrian city of Kalhu, located some thirty kilometres south of Mosul in the Nineveh plains of northern Mesopotamia, is a symbol of the truly exceptional richness of ancient Iraq. Between approximately 1350 BC and 610 BC it was an important city covering an area of about 350 hectares, and was for a time the capital of the Assyrian empire. Excavations at Nimrud first began in the middle of the nineteenth century, led by Austen Henry Layard, and continued until the 1870s with other archaeologists carrying out fieldwork there, including Hormuzd Rassam, William Loftus and George Smith. After the Second World War, several teams directed by British and Polish archaeologists opened new trenches and documented the site. Important fieldwork was also regularly carried out by the Directorate of Antiquities of the Republic of Iraq from the 1950s to the 1970s and from 1982 to 1992. The nineteenth- and twentieth-century excavations at Nimrud revealed some of the most important monuments of Assyrian art, such as reliefs, ivories and sculptures including a statue of Ashurnasirpal II, and colossal human-headed winged lions. The excavations led to the discovery of the

(313/314)

palaces of Ashurnasirpal II, Shalmaneser III and Tiglath-pileser III, temples dedicated to the gods Ninurta, Enlil and Nabu, and the city’s fortifications.

The site of Nimrud has been systematically destroyed by Daesh. This destruction commenced in March 2015 and took place in a number of phases: first, the demolition of the front façade of the North-West Palace using bulldozers, followed by further destructions on 2 April 2015 using explosives, and finally the levelling of the Ziggurat in October 2016 using heavy machinery. In mid-November 2016, the Iraqi armed forces liberated Nimrud from Daesh control. The initial assessment of the damage is as follows.

With the almost complete levelling of the Ziggurat, the greater part of which was bulldozed by Daesh, most of its features have been destroyed or buried in the rubble. All that remains now is a fraction of the mound, which once exceeded 34 metres in height. The militants have also inflicted damage to the nearby Ishtar Temple, destroying the lamassus (winged-bull sculptures) that were housed within the temple. The Nabu Temple, located in the south-eastern part of the Royal Palaces Complex, has been targeted and damaged. The entrance to the temple, including its fish-shaped flanking statues, has been totally destroyed. In the North-West Palace of Ashurnasirpal II, the most important parts that once remained have been utterly devastated using explosives. The main entrance to the palace, leading to the throne room, has been completely destroyed and the lamassu demolished. The wall reliefs and lamassu of the second gateway have also been damaged, with only one large wall relief remaining intact. Although the throne room, located on the palace façade, was not itself damaged by explosives, its contents, including wall reliefs, did experience destruction at the hands of Daesh, who used sledgehammers to destroy the interior. Of the tombs, only the first could be entered and documented by the assessment team. Although there was clear damage to its entrance, the interior of the tomb itself was found to be intact and undamaged.

At the site of Hatra, a city of the Parthian period (second century BC — second century AD), video footage circulated by Daesh shows them smashing sculptures, both freestanding and in the round, and decorative architectural elements. However, with the liberation of Hatra by Iraqi forces in May 2017 it appears that the damage is less than feared: these sculptures have indeed been smashed, but the principal buildings, such as the temple to the sun god, have not been destroyed.

In addition to the wanton destruction of sites, some have also been looted by Daesh for the antiquities they contain. Stopping the trade in antiquities is accordingly imperative. To quote Mohammad Iqbal Omar, Iraq’s Minister of Education, ‘We must stop the trade in Iraqi antiquities, adhere to Security Council Resolution 2199, and dry up Daesh’s money flow.’ As we reclaim our country’ said Fryad Rawandouzi, Minister of Culture, ‘we need help from UNESCO, the UN and others to rehabilitate museums, cities and sites, and return stolen objects. We need a plan with a timeline, as well as technical and financial support.’ Mohammad Iqbal Omar added ‘Daesh tried, but will never erase our culture, identity, diversity, history and the pillars of civilization. I call on the world to help us.’

Looking ahead, and with the support of programmes such as the British Museum’s Iraq Scheme, we may hope that the recovery and rehabilitation of Iraq’s ancient sites may feed into a better future for the nation. Iraq is a country with an incredibly rich heritage. It is the cradle of civilization, with a huge number of remains, both archaeological sites and standing monuments, the range of which extends from deep prehistory to the present day. As peace returns, archaeological expeditions, both Iraqi and international, are once again exploring this unique heritage. These researches will generate new insights into the rise and fall of the many civilizations which have flourished here. There is, moreover, a growing interest in tourism, both from neighbouring countries and from further afield. Effective and sustainable site management is essential if this is to develop and flourish.

|